Parler

Parler Gab

Gab

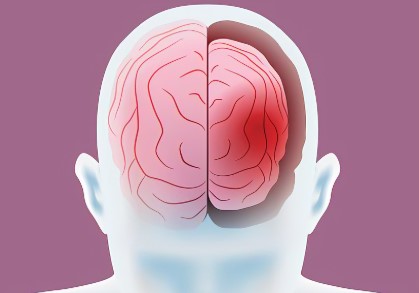

- Rare brain neurons that regulate blood flow are extremely vulnerable to chronic stress.

- This neuron loss reduces blood flow and disrupts brain activity.

- These effects are especially pronounced during critical sleep cycles.

- The findings suggest a biological pathway linking stress and Alzheimer's.

- Managing chronic stress may be essential for preserving long-term brain health.

The brain’s master regulators

The study reveals that this tiny population of neurons acts as a master conductor, orchestrating both blood flow and the coordination of electrical signals across different brain regions. Their death leads to a desynchronized brain, with poorer communication between hemispheres and diminished power in low-frequency brainwaves essential for cognitive function. This discovery provides a concrete mechanism for what health experts have long observed: chronic stress inflicts profound damage on the brain. It is not merely a feeling but a biological state that can reshape our neural architecture.A cascade of damage

The Penn State findings add a crucial piece to a larger, alarming picture of how stress compromises the brain. Uncontrollable stress triggers a flood of hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. While helpful in short bursts, chronic exposure suppresses the immune system, alters genetics, and interferes with tumor-suppressing genes. This hormonal onslaught leads to widespread inflammation, which is often said to be the root of all 21st-century diseases. Inflammation in the brain can negatively impact cognitive function and emotional well-being, leading to memory loss, depression, and anxiety. Furthermore, stress disrupts sleep, which is when the brain’s glymphatic system—a waste-clearance mechanism—is most active. Poor sleep prevents the clearing of neurotoxic proteins like amyloid, which are linked to Alzheimer's. Over time, this combination of inflammation, hormonal imbalance, and accumulated toxins is thought to accelerate brain aging, contributing to an earlier onset of cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases. The body’s stress response, designed for survival, becomes a slow-acting poison when constantly activated by the pressures of modern life. The takeaway is clear: Chronic stress is not a mere inconvenience but a direct assault on the brain’s structural and functional integrity. The loss of a handful of critical neurons could be the missing link explaining why a stressful life so often precedes a broken brain, making the active management of stress not just a lifestyle choice, but a non-negotiable pillar of brain health preservation. Sources for this article include: MedicalXpress.com ELifeSciences.org AmericanBrainFoundation.org UAB.eduGovernments continue to obscure COVID-19 vaccine data amid rising concerns over excess deaths

By Patrick Lewis // Share

Ultra-processed foods linked to surge in early-onset colorectal CANCER, study warns

By Patrick Lewis // Share

Social media use linked to lower reading and memory scores in children, new study finds

By Cassie B. // Share

A veil of secrecy: U.K. health agency withholds data amid excess death concerns

By Willow Tohi // Share

The silent rhythm of blood pressure: How daily habits shape your heart health

By Willow Tohi // Share

Personalized vitamin D supplementation halves risk of second heart attack, study finds

By Ava Grace // Share

Governments continue to obscure COVID-19 vaccine data amid rising concerns over excess deaths

By patricklewis // Share

Tech giant Microsoft backs EXTINCTION with its support of carbon capture programs

By ramontomeydw // Share

Germany to resume arms exports to Israel despite repeated ceasefire violations

By isabelle // Share