Parler

Parler Gab

Gab

- A 2024 study found that people consuming high levels of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) face a 53% increased risk of insomnia, with a 2023 Harvard study linking UPFs to reduced deep sleep.

- UPFs lack sleep-supporting nutrients like tryptophan, fiber, magnesium and antioxidants, while additives (e.g., artificial sweeteners, BPA) interfere with metabolic and hormonal regulation.

- Poor sleep triggers sugar and UPF cravings, exacerbating sleep disruptions. Studies show that switching to whole foods (e.g., Mediterranean diets) can improve sleep quality within weeks.

- UPFs now make up 50% of the average American diet, contrasting with pre-1950s minimally processed diets linked to lower chronic disease rates. Systemic changes (e.g., better labeling, whole-food access) are needed.

- Prioritizing vegetables, whole grains and home-cooked meals—while avoiding processed snacks—can restore sleep and health. Experts advise “progress, not perfection” in reducing UPF reliance.

The science behind the sleep-UPF link: Nutrient depletion and biological tampering

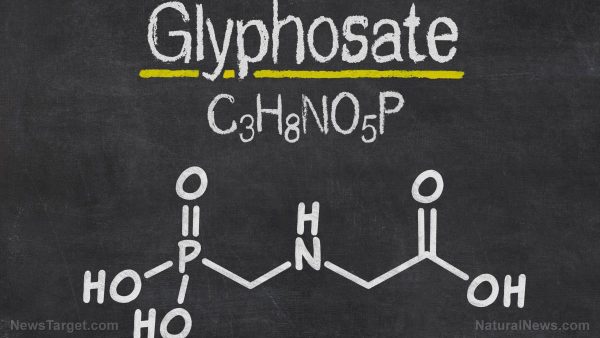

The disruption begins at the cellular level. UPFs are engineered to be hyperpalatable, but their nutrient profiles are stripped of essential sleep-supporting ingredients, said Seattle-based dietitian Angel Planells. Melatonin, the hormone regulating sleep, relies on tryptophan, which is scarce in processed foods. Moreover, UPFs lack fiber, vitamins like B6 and magnesium, omega-3s and antioxidants, all critical for circadian rhythm regulation. The Harvard study, published in Obesity, found that even short-term UPF consumption (one week) reduced slow-wave sleep—a deep, restorative phase critical for tissue repair and cognitive function. Overconsumption of refined carbohydrates and sugar also triggers blood sugar spikes and crashes, releasing stress hormones like cortisol that interrupt sleep. Additionally, additives such as artificial sweeteners and BPA-laden packaging have been linked to metabolic dysregulation and hormonal imbalances, further disrupting the body’s sleep architecture. Winters emphasizes that this is “no accident.” The spike in UPFs coincides with modern dietary shifts, where convenience overrides biology. “Two generations ago, food was real,” she noted. “Now, additives and artificial ingredients are biological disruptors.”The insomnia cycle—and how to break it

The connection between UPFs and sleep is bidirectional. Poor sleep intensifies cravings for sugar and processed snacks, fueling a vicious cycle. “When sleep is compromised, the brain seeks energy quick fixes,” said Planells. This interplay complicates recovery but also offers pathways for intervention. Evidence suggests that dietary changes can reverse sleep disruptions within weeks. A 2023 Wake Forest University trial showed that after seven days on a whole-food, Mediterranean-style diet, participants reported improved sleep duration and melatonin levels. “The body wants to heal,” Winters said. “It just needs the right biochemical language.” Transitioning away from UPFs requires strategic steps. Winters advises prioritizing “real foods”—vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins—while avoiding aisles stocked with packaged snacks. Home cooking, snacking on nuts or fruit and choosing complex carbohydrates (oats, quinoa) instead of refined grains can reduce reliance on UPFs.Moving forward with historical context—a return to dietary normalcy

The rise of UPFs mirrors broader societal changes since the mid-20th century, when industrial food production boomed. Before the 1950s, diets were far less processed, and chronic diseases like diabetes and insomnia were rarer. Today, UPFs dominate due to convenience and affordability, but their impact on sleep and health is becoming impossible to ignore. Public health advocates argue that reversing trends requires systemic shifts—from stricter food labeling to subsidizing fresh produce in underserved areas. The NOVA food classification system, which categorizes UPFs as “formulations,” helps consumers navigate supermarket choices. Schools and workplaces, meanwhile, can pivot their offerings toward whole foods to alleviate dependency on vending-machine snacks.A remedy as old as nutrition—good food, better sleep

The evidence is clear: balancing sleep and health demands rejecting the “science experiments” masquerading as food. As the Harvard study reminds us, sleep disruption is a tangible cost of UPF-heavy diets. Yet, the solution is within reach: prioritize nutrient-dense meals, hydrate, foster sleep hygiene and resist incremental dietary compromise. “Progress, not perfection,” echoed Planells. For a culture steeped in quick fixes, embracing this mindset might just be the first step toward reclaiming rest—and rebalancing health in an era of processed excess. Sources for this article include: TheEpochTimes.com MDPI.com Health.Harvard.eduAyahuasca: This Amazonian brew may be the most powerful antidepressant ever discovered

By News Editors // Share

The history of Frankincense: From ancient rituals to modern home fragrance

By HRS Editors // Share

U.S. Health Secretary: Chemtrails are real and must be stopped

By S.D. Wells // Share

Study shows oral health could be key to preventing heart disease

By Cassie B. // Share

Governments continue to obscure COVID-19 vaccine data amid rising concerns over excess deaths

By patricklewis // Share

Tech giant Microsoft backs EXTINCTION with its support of carbon capture programs

By ramontomeydw // Share

Germany to resume arms exports to Israel despite repeated ceasefire violations

By isabelle // Share